Confronting My Own Climate Bystander & the Labyrinth of Inaction

It began not with a flash of insight, but with a slow burn of discomfort: a feeling I believe resonates with many. The headlines about climate change were a daily drumbeat, the scientific consensus undeniable, yet I found myself, like so many others, caught in a strange state of informed paralysis.

I was a 'climate bystander'.

Living in India, where the spectre of climate impact looms large, from unpredictable monsoons to soaring temperatures, this passivity felt increasingly untenable. The question that lodged itself in my mind during my Master's studies at the National Institute of Design wasn't just why this collective inaction persisted, but a more personal one: what could I, as a designer, possibly do to pierce this veil of normalcy?

This line of inquiry became the genesis of Carbon Block, my thesis project.

It wasn't conceived as the solution, but as my attempt to understand and perhaps disrupt this bystander phenomenon, starting with myself. This is the first of the series of posts that chronicles that journey.

Today, I want to take you deep into the initial labyrinth of research, into the complex, often unsettling reasons for our collective inertia, and share some of the critical questions I grappled with even as I tried to define the problem.

The bystander effect illustrates how individuals are less likely to offer help to a victim when other people are present, as responsibility diffuses across the crowd and leads to a pluralistic ignorance.

The Weight of the World: Why We Stand By

Unpacking the "climate bystander" effect meant going far beyond individual psychology. I found myself immersed in a web of interconnected issues, each reinforcing the others, making the path to action seem almost impossibly convoluted.

| Living in a Carbon-Cobwebbed World

My readings, particularly the work of scholars like Andreas Malm in Fossil Capital, revealed how deeply entrenched the fossil fuel paradigm is. It’s not just an energy source; it’s the historical bedrock of our industrial-capitalist society. Malm’s analysis of the shift to coal in the 19th century, for instance, wasn't primarily about its efficiency over water power, but about its controllability and capacity for centralized profit — qualities that have shaped our economic and social structures ever since.

This has created what I came to see as a 'carbon cobweb': vast infrastructures, global supply chains, financial systems, political lobbying, and even our daily routines are all intricately tied to this carbon-intensive path.

The sheer scale of this interconnectedness fosters a sense of systemic lock-in. To challenge it feels like trying to unravel the very fabric of modern life, a task so daunting it often leads to resignation.

| The Elephant in Every Room: Wealth, Consumption, and Glaring Injustice

The uncomfortable truth, underscored by reports from organizations like Oxfam and the meticulous economic analyses of researchers like Thomas Piketty and Lucas Chancel, is that the burden of responsibility for climate change is wildly unequal.

I remember being particularly struck by the recurring statistic: the wealthiest 10% of the global population are responsible for roughly 50% of total lifestyle consumption emissions, while the poorest 50% (who often face the harshest climate impacts) account for a mere fraction, around 12%.

The UN Environment Programme consistently points to this hyper-consumption by the affluent as a primary driver. This isn't just an economic statistic; it’s a moral chasm. It means that those who benefit most from the systems driving climate change are often the most insulated from its immediate effects, while those with the least power and fewest resources are on the front lines.

This disparity not only fuels resentment but also complicates global negotiations and equitable solutions. How do you ask for universal sacrifice when the starting lines are so vastly different?

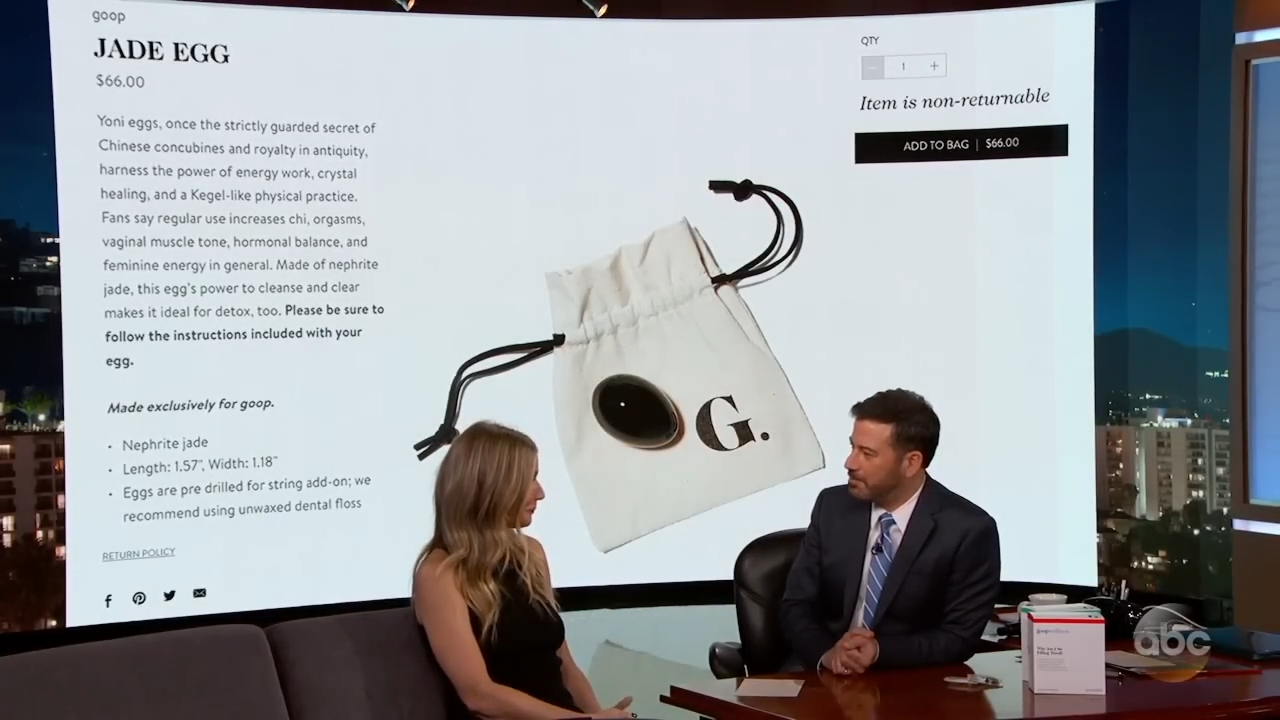

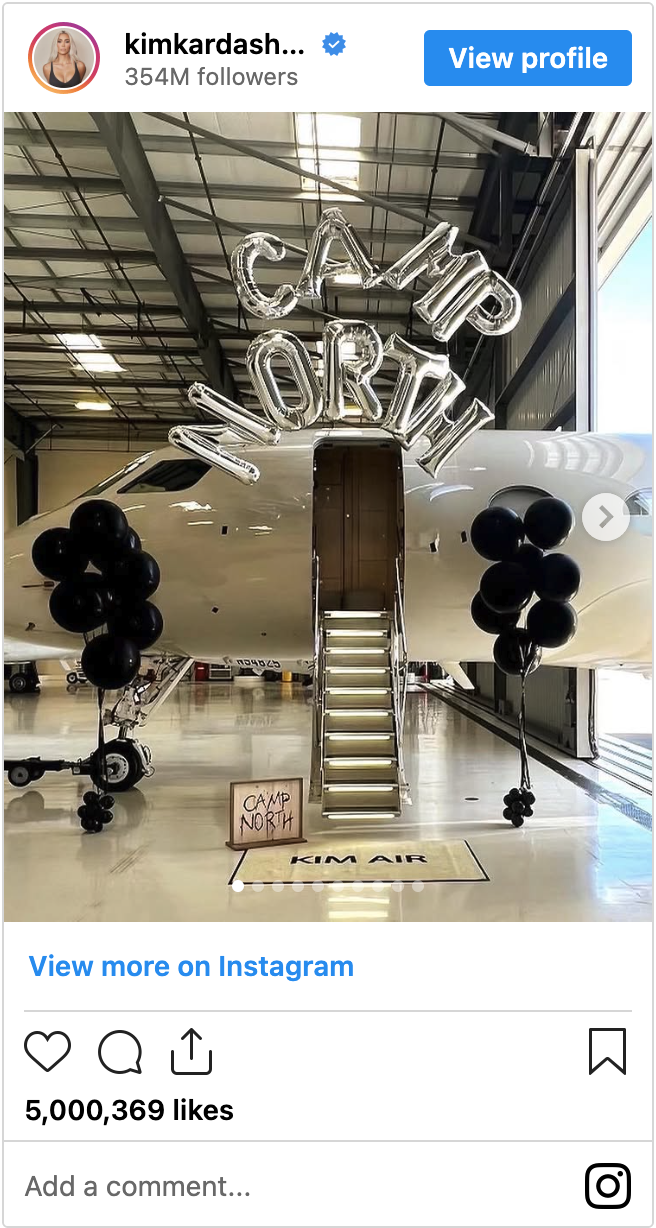

Moreover, the social media amplifies elites' consumption as the standard of "success," glamorizing environmental costs and trapping lower classes in upward comparison, turning the carbon-heavy lifestyle of the few into the unsustainable dream of many.

| The Persistent Ghost of Malthus: Deconstructing the Population 'Myth'

It’s a narrative I encountered repeatedly, both in casual conversations and in more formal discourses: "There are just too many people!"

But as authors Ian Angus and Simon Butler meticulously argue in Too Many People? Population, Immigration, and the Environmental Crisis, this focus on sheer numbers is often a dangerous oversimplification, a convenient way to deflect attention from the core issues of resource distribution and consumption patterns.

Historically, Malthusian arguments have been used to justify social inequalities and resist systemic change. While rapid population growth can indeed strain resources locally, the global environmental crisis is disproportionately driven by the high-impact lifestyles prevalent in wealthier nations and among the global elite, regardless of population density. Also, Malthusianism has often been criticized to not account for technological advancements, which widens the power balance even further by giving more advantage to the elites who are often wielders of them.

Acknowledging this doesn't mean ignoring demographic challenges, but it forces a shift in focus towards equity and sustainable consumption for all, rather than blaming the vulnerable.

| The Inner Landscape: Our Psychological Stumbling Blocks and Cultural Silences

Beyond the systemic issues, I had to confront our own human nature. George Marshall’s Don't Even Think About It: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Ignore Climate Change was a revelation. He lays out how our cognitive architecture, evolved for immediate, tangible threats, struggles with a slow-moving, abstract crisis like climate change. We're prone to optimism bias ("it won't be that bad for me"), confirmation bias (seeking out information that supports our existing views), and discounting the future.

This is further compounded by what sociologist Kari Norgaard, in Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life, describes as "socially organized denial." Through her study of a Norwegian community, she showed how, even when people are intellectually aware of climate change and express concern, communities can collectively participate in practices that normalize inaction and silence discussion to avoid emotional discomfort. It’s a subtle, pervasive form of denial that’s not about outright rejection of facts, but about a collective 'looking away.'

And then there's the sheer scale of it. Timothy Morton calls climate change a ‘hyperobject’: a phenomenon so vast in its temporal and spatial dimensions, so massively distributed and complex, that it defies easy comprehension and traditional modes of response. It’s everywhere and nowhere, making it incredibly difficult to pinpoint responsibility or envision a clear path to resolution.

Social denial spills into politics: Leaders ignore scientific data and favor short-term gains over long-term action. That creates a loop where the public shifts responsibility to politicians, and politicians shift it back to the public. [AI generated image]

Grappling with the Gaps: My Own Critical Questions at the Outset

As designer, we are often trained to identify our biases in a our research and suspend our judgement to look beyond what seems obvious. Even as my understanding of the problem deepened, so did my awareness of potential pitfalls in my own framing. I asked myself:

Was the "bystander" label itself too simplistic? While it captured a sense of passivity, did it adequately account for the vast differences in agency? The "choice" to act for someone struggling with basic needs in a climate-vulnerable region is vastly different from that of an affluent individual in a developed nation with multiple sustainable options. Was I at risk of individualizing a problem that my research clearly showed was deeply systemic?

In focusing on an "alarm," was I underestimating the need for profound systemic overhaul? A nudge, an alarm – these are valuable, but can they truly stand against the inertia of the fossil economy or the deeply entrenched inequalities I was learning about? I worried about the potential for such interventions to become mere palliatives, creating a feeling of action without addressing the root causes.

Were there cultural nuances I was missing? My research drew heavily on Western academic sources. While the psychological and economic analyses felt broadly applicable, I wondered if the expression and experience of 'bystanderism' or 'denial' might manifest differently across diverse cultural contexts, especially within India. How could any intervention be truly resonant without a deeper appreciation of these local nuances?

I was focusing on awareness and nudging, but what about enabling concrete action? If my alarm did wake someone up, what then? Was a lack of awareness the sole, or even primary, barrier, or was it also a lack of accessible, viable alternatives and a feeling of political powerlessness?

These questions didn't have easy answers, and they lingered with me throughout the project. They served as a constant reminder that any design intervention, especially in a space as complex as climate change, must be approached with humility and a keen awareness of its own limitations.

The Path Ahead: Giving ideas a form

This initial phase of research was like mapping a vast, dark forest. I had identified some of the major trees, the challenging terrains, and even some of the creatures lurking within (both systemic and psychological). I also had a clearer sense of the questions I needed to keep asking myself. The weight of the problem felt immense, but the desire to find a meaningful point of intervention, however small, had only grown stronger.

The next step was to try and distill these complex, often contradictory insights into a more focused design brief. How could I move from broad understanding and speculative provocations to a tangible concept that could actually function as an "alarm" in people's lives?

I will see in the next post as I delve into that messy, iterative process of design: the brainstorming, the metaphors that emerged, the debates over form and function, and how these eventually coalesced into the concept of the 'Carbon Block'.