There was a time when most websites would beg their users to take a quick survey or rate their experience with little stars (this is still relevant for mobile apps). We clicked “Remind me later” or ignored pop-ups, and moved on. Behind the scenes, companies silently collected loads of telemetry data – page-load times, click paths, error logs – to figure out what went wrong.

This blend of explicit feedback (surveys, bug reports, star ratings) and passive monitoring (performance telemetry, click analytics) has been the bread and butter of improving products. UX researchers often say “user feedback is gold” for understanding real needs , and indeed, gathering it helped companies boost usability and customer happiness.

In fact, the End User Experience Monitoring (EUM) industry – which focuses on tools to track user-facing performance – has exploded: estimates put the global EUM market at about $3–5 billion today, growing to $8–11 billion by 2030–31. These tools let dev teams see where pages lag, where errors spike, and where users get stuck , so they can fix issues before customers even complain.

But let’s be honest: most of this feedback work tends to reward the company more than the user. We patch bugs, speed up pages, and roll out features, often under the assumption that happier customers eventually mean more revenue. Meanwhile, the folks actually giving feedback rarely see a dime. They might get bragging rights (“You helped make the product better!”), but that’s about it.

Enter Generative AI: A New Feedback Landscape

Fast forward to today’s world of generative AI, and the feedback game has changed drastically. Unlike traditional software (which is deterministic – same input leads to same output every time), models like ChatGPT or DALL·E are probabilistic and creative. As one AI researcher notes, a single input prompt can yield many different reasonable responses because the model operates on probabilities, not fixed rules.

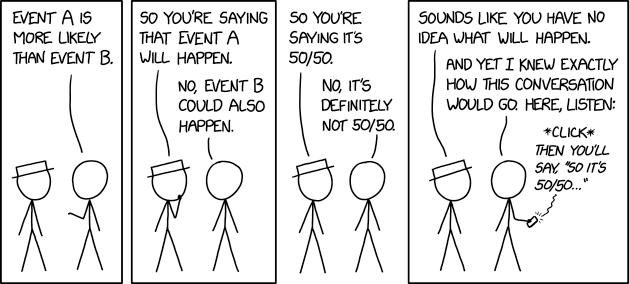

This comic strip by xkcd loosely illustrates how non-determinism works on statistical probabilities rather than fixed/defined path.

This non-determinism means outputs vary with each run – a feature that sparks imagination but also unpredictability. For example, type the same question twice and get two different answers, or even bizarre “hallucinations” of made-up facts. In other words, AI often asks us whether its answers are good or not, because its “ground truth” is fuzzy. In fact, many AI teams admit that user satisfaction is often the most important metric for generative models, since there isn’t a clear-cut correct answer.

This is where feedback moves from “nice to have” to mission-critical. AI developers now rely heavily on user signals to refine their models. OpenAI’s approach to aligning GPT with our values, for example, involves Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF). In plain terms, that means after pretraining a model on text, they gather human preferences (like which answers they liked better) and use that as a custom reward function to fine-tune the model. Even daily interactions can become training data: thumbs-up or thumbs-down ratings on ChatGPT are fed back to influence future generations.

Thumbs-up, thumbs-down and copy text icons appear after every reply from ChatGPT. [May 2025] A recent data-science blog even illustrated this with ChatGPT’s UI: thumbs up/down as explicit, and a “copy” click as an implicit hint.

And it’s not just explicit ratings. AI systems also harvest implicit cues: Did the user edit the prompt and try again? Did they copy-paste the result or immediately hit “Regenerate”? Explicit feedback is things like star ratings, “Was this answer helpful?” buttons, or written comments. Implicit feedback is more subtle: it could be measuring time spent on an answer, tracking whether people hit “copy to clipboard,” or analyzing how much they edit the AI’s output. Each of these signals offers a piece of the puzzle about the user’s experience with the AI.

Feedback for digital applications can be arranged into this matrix where they vary based on UX type (deterministic vs non-deterministic systems) and the nature of feedback collection (explicit vs implicit).

Because generative AI lacks a single correct answer, these human signals become the currency of improvement. In short, we’ve moved from tracking page load times to tracking satisfaction rates and edit histories.

With feedback now so pivotal to AI’s evolution, some have asked: Should we reward users for giving it?

The Case for Incentives

There are some compelling arguments in favor of the idea:

1. More and better data: Offering incentives typically boosts response rates. For example, industry reports note that giving rewards dramatically increases the volume of reviews or feedback companies receive. If every thumbs-up or correction carried a small bounty (points, credits, discounts, whatever), more users might bother to share their thoughts. More data can only help the AI get better faster. (In crowdsourced tasks like image-labeling or user-testing, paid workers often churn out higher quantities of data.)

2. Quality improvements through reciprocity: Many people already give feedback out of altruism or a sense of community like buyers do for lesser known brands/sellers on eBay/Amazon/Flipkart. But in a profit-driven tech world, it seems only fair to give something back. Paying users (even a tiny amount) or offering perks acknowledges that their input has real value. One AI ethics commentary argues that crowd workers deserve fair pay and rights if their work underpins the model. It’s a modest “thank you” for helping train a system they enjoy using. This reciprocity can build goodwill: users feel respected rather than exploited.

An example profile page on eBay showing a sellers reputation score card and feedback history

3. Engagement & trust: Gamified rewards (badges, points, exclusive access) can create a vibrant feedback culture. Platforms like StackOverflow and open-source projects thrive on peer recognition; one economics study found that peer votes significantly increased contributions in a Q&A community. If thoughtfully designed, incentive schemes could similarly galvanize AI users to participate actively. The promise of earning status or rewards may even attract diverse voices who wouldn’t speak up otherwise. Ultimately, a trusted feedback loop – where users see their contributions influence updates – can strengthen the product.

4. Ethical fairness: In some ways, paying for feedback aligns with an ethical view of data: if a company’s AI becomes valuable thanks to your conversations, shouldn’t you get a cut? After all, the rise of data privacy and user-consent laws shows that organisations can’t just grab feedback for free without some quid pro quo.

The Case Against Incentives

On the flip side, incentivizing feedback can backfire in several ways:

1. Spamming and gaming: Any time money or points are on the line, some people will try to cheat. If users get paid per feedback, they might submit fake or low-effort responses just to earn rewards. Studies of paid online reviews show exactly that pattern: users offered money tend to write shorter, less informative reviews and lean positive. And once system-savvy users realize how to optimize reward, the signal-to-noise ratio of the feedback pool could plummet. Companies might end up wading through a flood of garbage feedback, ironically making product improvement harder, not easier.

2. Eroding intrinsic motivation (the overjustification effect): Psychologists caution that external rewards can undermine natural goodwill. The overjustification effect describes how adding money to an activity people already enjoy can make them less motivated by the intrinsic satisfaction of helping.

The anticipation of a reward rather than the mere existence of a reward—seems to have an important influence on the overjustification effect.

3. Positive bias and credibility loss: Paid feedback often skews positive which can give a misleading picture of the AI’s performance. Over time, knowing “These reviews were bought!” can undercut trust.

4. Cost and compliance headaches: Putting money on the table isn’t free. Companies would need to budget for this or, more likely, factor it into pricing (meaning the user might pay more for the service). There’s also the sticky question of labor law: at what point does a “feedback contributor” become an employee or contractor entitled to benefits? And don’t forget tax and payment processing overhead. Regulatory frameworks might also apply if incentives are financial. This would be a logistical and legal nightmare.

5. Privacy and fairness concerns: Incentive schemes may not reach all users equally. Some might be barred (e.g. minors) or uninterested in participating, raising fairness questions.

Finding the Middle Ground

This situation is complex. Thoughtful feedback incentives can be reasonable. Small rewards (loyalty points, badges, raffles) acknowledge user effort without making it transactional. Rewarding limited feedback shows respect and encourages insights. However, incentive systems need careful design. Combining extrinsic rewards with community-building helps preserve intrinsic motivation. Monitoring for spam and clarifying feedback importance might help mitigate abuse.

Transparency is vital; users must know how their data and feedback are used. It’s a trade-off: unpaid feedback may deprive AI of human insight, but careless payments can lead to biased input. The design and intent behind incentives matter. UX designers should consider these factors and test strategies.

A hybrid approach could work best: gamify feedback, offer small (non-cash) rewards for detailed reports, and include community recognition. Giving a small token of appreciation for aiding algorithm training is reasonable if transparent and monitored. Balancing incentives will ensure genuine feedback, but YES! We designers and product owners need to think about this sooner than later.