Our second semester started with the course Science and Liberal Arts II: An Approach to Indian Society. The course essentially gave us a brief introduction about Indian society from a historical, political, socio-economical and cultural level. As young designers, we are expected to understand and comprehend the consequences of our design decisions and policies on a societal level. The course intended on laying a foundation for our subsequent courses like Ethnography, Public Policy, Innovation & Design, etc. The course syllabus was not as extensive as that of civil service aspirants, but enough to make an uninitiated mind start thinking. From a Design perspective, I felt that it was more important than ever.

Our instructor Dr Mihir Bholey, as he started his first class said: In order to understand and approach the Indian society, one has to leave aside his personal prejudices and biases. His instructions were not unfounded. With a cultural spectrum as wide as that of India, one can get easily lost behind the rationale and peculiarities of various traditions and practices, in the myriad beliefs and social structures and quickly arrive at judgments. These judgments might be right or wrong, but as an Indian it is very important for us to understand, to actually know about ourselves as individuals, about our upbringing, about our privileges and our biases.

We have all been singing the notion of 'Unity in diversity' in India since our childhood. We are not oblivious to the fact that India has the widest spectrum of cultures, languages, cuisines, landscapes, etc. than anywhere in the world. We are different from each other and from the world. But what unified the citizens of this nation together? The answer is not one and it's certainly not simple. The reason, though very much perceivable to anyone living here, is not readily visible. Very much like the soul and the body. And though the questions pertaining to this bizarre confluence is unanswerable even by the wisest, its presence cannot be denied. To me, India seems to be the stratified settlement of various historical sediments, so much so that not one of them was able to completely eradicate or eclipse the existence of others. Many would agree that ‘Indian society is in a continuous process of evolution’. This process is more evident if one delves deeper into the history of India. Modern India is hence essentially a nation with deep and rich ancient history and culture, trying to come in terms with its growing population and mediocre infrastructure, which just after 70 years of independence is competing economically with some aggressive neighbours and the rest of the world. What seems to have been the changing agents of this vast nation plays a balancing and a counter-balancing effect on its various social, political, religious and economic aspects, some of which are mentioned below:

- Indus valley civilization and Aryan migration | ~3300 – 1300 BC

- The Vedic Era & Dawn of Buddhism | ~1500 – 1100 BC

- Islamic invasion and Delhi Sultanate | 1206–1526

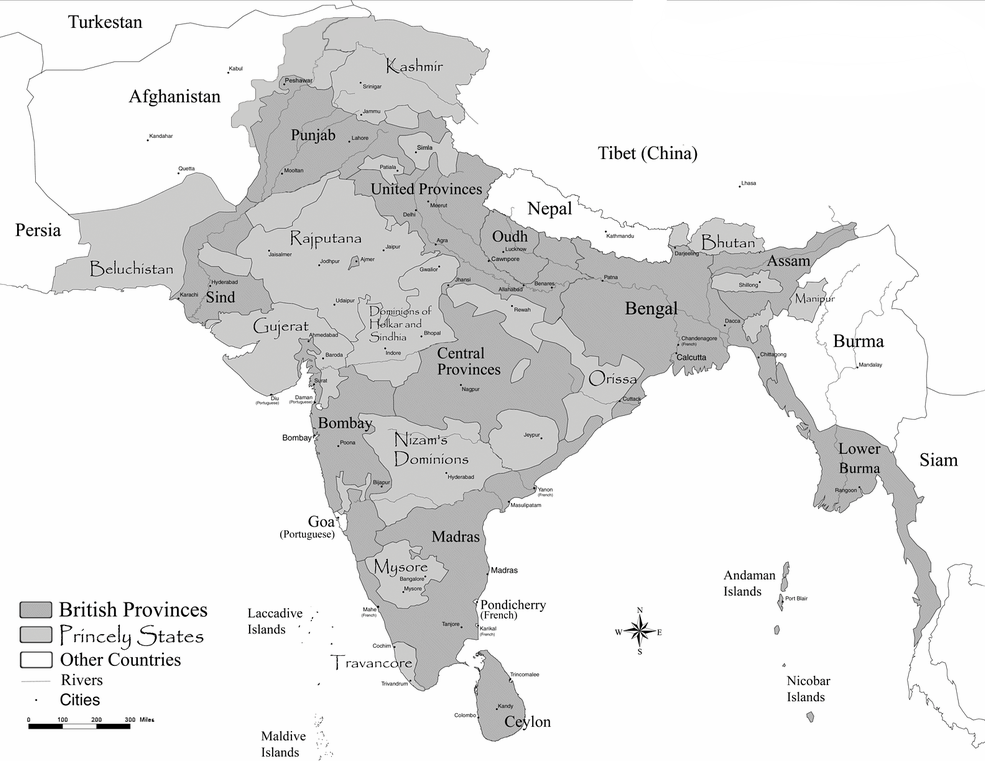

- Arrival of European traders and British colonisation | 1765-1947

- Freedom struggle and Independence | 1857-1947

- Economic liberalisation and globalization | 1990

Some changing factors that were talked in-depth were:

The Caste-System and other Socio-Political frameworks in Indian society

The Aryans brought with them a new language, a new pantheon of anthropomorphic gods, a patrilineal and patriarchal family system, and a new social order, built on the religious and philosophical rationales of varnashrama dharma. Although precise translation into English is difficult, the concept varnashrama dharma, the bedrock of Indian traditional social organization, is built on three fundamental notions: Varna (originally, "color", but later taken to mean social class), Ashram (stages of life such as youth, family life, detachment from the material world, and renunciation), and Dharma (duty, righteousness, or sacred cosmic law). The original three-tiered society--Brahman (priest), Kshatriya (warrior), and Vaishya (commoner) -- eventually expanded into four in order to absorb the subjugated people--Shudra (servant) -- or even five, when the outcaste peoples are considered.

The notion of the Jajmani system was popularized by colonial ethnography. It tended to conceptualize agrarian social structure in the framework of barter exchange relations. In its classical construct, different caste groups specialized in specific occupations and exchanged their services through an elaborate system of division of labour. Under the jajmani system, the kameen remains obliged to render the services throughout his life to a particular jajman and the jajman, in turn, has the responsibility of hiring services of a kameen. They often take part in the personal and family affairs, rituals and ceremonies. The jajmani system has gradually decayed in the modern society. The modern economic system that measures everything in terms of its monetary value, the decline of belief in the caste system and hereditary, a growth of better employment opportunities outside the village and introduction of new transport options has given a strong blow to the system.

Over several decades since the 20th century, several attempts were made by likes of Britishers, Mahatma Gandhi, Bhimrao Ambedkar, etc to diffuse this cultural tension but even post-Independence the caste system is still prevalent among the masses. In 2006, the 93rd Constitutional Amendment added clause (5) in Article 15 which stated-nothing shall prevent the State from making any special provision, by law, for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or for the Scheduled Castes or the Scheduled Tribes in so far as such special provisions relate to their admission to educational institutions including private educational institutions, whether aided or unaided by the State, other than the minority educational institutions.

Political Modernization of India

Almost all the political systems have set before themselves the goal of modernization. The political trends in India since independence have largely been a series of reconciliations with demands articulated by regional interest groups: linguistic formation of states in the political realm, emphasis on mixed economy in the sphere of economic policy, secularism and neutrality in international relationships are all reflections of the predominantly reconciliatory pattern of political modernization in India.

The same pattern is true in case of traditional institutions role in politics, caste associations, kin groups and ethnic solidarities have adapted themselves to the need of a modern democratic political culture successfully. Due to the impact of modern forces, certain changes have been witnessed in the political sphere of society. Regulation of court laws, the establishment of village panchayats and local autonomy has changed the traditional Indian political system. In villages, there is a decline of caste panchayats and their functions are being transferred to courts.

On the other hand, caste is developing on political lines. There is a change in the pattern of leadership. This leadership is now available to low-income groups as well. The predominance of all India parties indicates the extent to which political unity is firmly established. Regional differences of culture and language have found political expression in debates on the number and delimitation of states. It is evident from various sources that intellectuals in a broad sense have dominated political life in India since independence and that active participation in politics by the mass of the population such as occurred in the independence movement has recently begun to revive on a limited scale with the emergence of peasant movements in some states.

The reservation of seats for scheduled castes and tribes has led to the emergence of parties catering exclusively this section of society. In recent years they have made huge gains both in term of vote share and role in the national politics. There are conflicts between traditional social arrangements, caste system and religion and new relationships brought out by economic growth.

Decentralisation and Rural Governments in India

Decentralization can be defined as transfer or dispersal of decision-making powers, accompanied by a delegation of required authority to individuals or units at all levels of the organization even if they are located far away from the power centre. In the context of the present discussion, decentralization signifies the devolution of powers and authority of governance of the Union Government and State Governments to the sub-state level organizations i.e. Panchayats in India.

In the course of the freedom movement, it became clear that after independence India’s nationhood would evolve within a democratic political and institutional setting. Some leaders believed that it should be a representative democracy much in the mould of western countries. But Mahatma Gandhi’s development discourse hinged on a village-based participatory democracy embedded in his vision of the Panchayati Raj. Gandhi felt that real development of India can take place only through its political system of Gram Swaraj in which the State Government would only exercise such powers which are not within the scope and competence of the lower tiers of participatory governance institutions. The journey towards political and administrative decentralization started with the recommendations of the Mehta Committee. All the states enacted Panchayat Acts and by 1960 Panchayats were established throughout India. But these steps could hardly change ground realities as laws were weak and inexplicit. Local administrations resisted devolution of functions and powers, regular elections to Panchayati institutions were not held.

The country experienced significant political changes during the mid-1970s, with which the process of resurrection and strengthening of Panchayati Raj System regained momentum. Many State Governments delegated authorities and schematic funds to the Panchayats for implementing various development programmes. But in the absence of appropriate statutes defining the role, functions, duties, authorities and powers, the Panchayats were not successful enough to ensure de facto involvement of people in development programmes. It was argued that instead of leaving the issue entirely at their discretion, the states had to be bound by some constitutional mandate.

This led to the 73rd amendment of the Constitution in 1992, given effect from April 24, 1993. This landmark amendment of the Constitution declared the Panchayats as units of self government, directed the states to devolve functions of 29 subjects directly related to social and economic development of an area, made provisions for resource sharing between the Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) and Governments, regular elections to local bodies, reservation of socially disadvantaged classes and women etc.

Structural Changes in Indian Economy

Immediately after independence and especially after the launch of the first 5-year plan, the then Government of India launched massive development projects on one hand and Community Development (CD) Programmes and National Expansion Services for rural development, on the other. Apart from the growth in quantitative terms, there have been significant changes in India’s economic structure since:

The table shows that the share of the agriculture sector to national income has been constantly decreasing. The history of economic development of advanced countries indicates that the contribution of agricultural sector to national income goes on decreasing as the country develops. The increasing share of industrial sector shows that Indian economy is on the way of development. The contribution of the industrial sector is very high in developed countries like U.K. and U.S.A. In India, though the contribution of the industrial sector is increasing, its progress is very slow. Especially the share of manufacturing within the industrial sector has been very slow since 1970-71. This is mainly responsible for the slow rate of economic growth in the country.

When country attained independence, the share of basic and capital goods industries in the total industrial production was roughly one-fourth. Under the Second Plan, a high priority was accorded to capital goods industries, as their development was considered a pre-requisite to the overall growth of the economy. Consequently, a large number of basic industries which produce capital equipment and useful raw materials have been set up making the country’s industrial structure pretty strong.

The tertiary sector or service sector has been constantly increasing its share in the national income. It includes transport, communication, trade and commerce, banking, insurance, community and personal services. It shows the development of infrastructure in the economy. In advanced countries, the contribution of the service sector to national income is the highest. The railway route length increased by more than 9 thousand kms and the operational fleet practically doubled. The Indian road network is now one of the largest in the world as a result of the spectacular development of roads under various plans. India has also seen growth in life- expectancy and literacy rate but education has not expanded at the desired rate.

Since independence, significant progressive changes have taken place in the banking and financial structure of India. The growth of commercial banks and cooperative credit societies has been really spectacular and as a result of it, the importance of indigenous bankers and money-lenders has declined.

Government Initiatives (2005-)

- Right to Information Act, 2005 ensures that the people we put in power remain answerable to the citizens always and by no means can they use public funds arbitrarily. It is one of the most powerful legislation in the hands of the people that empowers them to seek information from the government. The RTI Act mandates timely response to a request for information from a public authority.

- Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) of 2005 is a rural wage employment programme in India. It provides for a legal guarantee of at least 100 days of unskilled wage employment in a financial year to rural households whose adult members are willing to engage in unskilled manual work at a pre-determined minimum wage rate.

- The Government announced Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana as the National Mission on Financial Inclusion to ensure comprehensive financial inclusion of all the households in the country by providing universal access to banking facilities with at least one basic bank account to every household, financial literacy, access to credit, insurance and pension facility. Under this, a person not having a savings account can open an account without the requirement of any minimum balance and, in case they self-certify that they do not have any of the officially valid documents required for opening a savings account, they may open a small account.

- Stand Up India scheme caters to promoting entrepreneurship amongst women, SC & ST category i.e those sections of the population facing significant hurdles due to lack of advice/mentorship as well as inadequate and delayed credit. This enterprise may be in manufacturing, services or the trading sector.

- The NITI Aayog (National Institution for Transforming India), is a think tank of the Government of India established on 1 January 2015 as a replacement for the Planning Commission to provide Governments at the central and state levels with relevant strategic, directional and technical advice across the spectrum of key elements of policy/development process (eg. special attention to marginalised sections who may be at risk of not benefitting adequately from economic progress, on technology upgradation and capacity building etc.) In addition, the NITI Aayog will monitor and evaluate the implementation of programmes.

- Swachh Bharat Abhiyan also called the Clean India Mission or Clean India drive or Swachh Bharat Campaign is a national level campaign run by the Indian Government to cover all the backward statutory towns to make them clean. This campaign involves the construction of latrines, promoting sanitation programmes in the rural areas, cleaning streets, roads and changing the infrastructure of the country.

The above arguments cover the scenario from a Post-Independence point of view. But, our society has experienced this turbulence of change in all spheres of life since the beginning of the civilizations and has been very successful in adapting to them. For now, the advent and mass exposure of ever-changing technology have created both opportunities and new challenges for the modern Indian society. We are not sure what will happen next, but we can be sure that ‘change is evident’.